How I Rack and Stack: Inside My Lesson Planning Brain

In the past I have been asked, “How do you decide which EduProtocols to use, and how do you stack them together?”

On the surface, a rack and stacked lesson looks like it just works. Kids are engaged and the transitions are smooth. But there’s a lot of planning behind that flow. Decisions that start long before the first Gimkit or Frayer Model ever hits the board.

So I thought I’d pull back the curtain a bit and walk through how I build these lessons. I’ll use two real examples: one on Manifest Destiny (Mini Report too), and the other on Andrew Jackson and the Nullification Crisis. Different months, different topics, but the same planning approach.

It’s not just about which EduProtocols I like. It’s about what kind of thinking the content demands, and what kind of thinking I want students to practice.

Start with the End in Mind

Every lesson starts with one question: What should students know or be able to do by the end of this?

For Manifest Destiny, I wanted students to understand the concept and controversy of the idea—why people believed in it, what it looked like, and how it’s viewed today. They needed to analyze both visual and written sources and make comparisons between historical and modern perspectives.

For the Nullification Crisis, the goal was to understand how tariffs sparked tension between state and federal power, and to analyze Jackson’s leadership through that conflict. This wasn’t about memorizing dates—it was about understanding motivations, perspectives, and consequences.

The learning targets were content-specific, but they were rooted in bigger historical thinking skills: sourcing, analyzing POV, sequencing causes and effects, and making comparisons.

Build the Stack Around Thinking, Not Just Activities

Here’s where the rack and stack comes in. I don’t start with a random list of EduProtocols. I think about how the brain learns (I’ll fully admit, no clue if these terms are correct, but it’s how I think about them):

Retrieval, Fluency, Context, Synthesis, Expression

That learning arc helps me organize the protocols in a way that makes sense.

My coauthor Scott Petri would always stack (sequence) EduProtocols in a way to help students create something/express themselves at the end of a lesson. An example of this is his use of Fast and Curious and Thin Slides throughout a lesson that would build to the Thin Slides being used for an Ignite Talk.

Manifest Destiny Stack

Fast & Curious: Vocabulary primer to retrieve key terms

Wicked Hydra: Generate questions from a controversial headline to spark curiosity

Sourcing Parts: Analyze the “American Progress” painting to tackle symbolism and sourcing

MiniReport: Synthesize a textbook excerpt and a modern article into a structured comparison

Nullification Crisis Stack

Fast & Curious: Start again with vocabulary retrieval

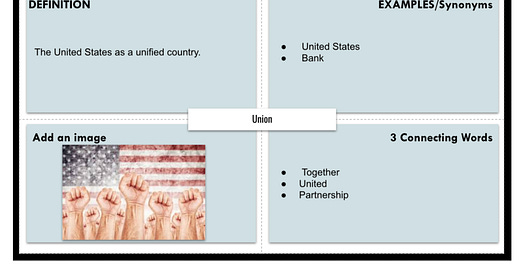

Frayer Model: Use student data to target the most-missed terms for clarity and fluency

Somebody-Wanted-But-So-Then: Sequence the conflict with a narrative lens

2xPOV: Explore Jackson vs. Calhoun’s stances through primary source excerpts

The protocols change, but the pattern doesn’t. Start with retrieval, build into context and complexity, and finish with a chance for students to show their creativity/knowledge.

Let the Content Shape the Thinking

The thinking flow stays the same, but I adapt it based on what the content demands.

Manifest Destiny is full of imagery, myth, and legacy. It asks students to wrestle with beliefs, intentions, and consequences. I use EduProtocols that bring those pieced to life through visuals, structured writing, and modern-day connections.

The Nullification Crisis, on the other hand, is rooted in power dynamics and constitutional interpretation. It’s about understanding who wanted what, why they clashed, and how it played out. So I lean into story structure and POV work to help students break it down.

I’m not asking, “Which protocols do I like?” I’m asking, “What kind of thinking does this content require?”

Some Skills Go Beyond the Content

There’s another layer here, too. Sometimes it’s not just about history skills, it’s about cognitive skills that matter long after students leave the classroom. I’m trying to take care of the present while preparing kids for the future.

Here are three skills I intentionally built into these stacks:

Adopting a Different Perspective: The POV Analysis protocol pushed students to consider two very different interpretations of the same conflict: Jackson and Calhoun’s views on states’ rights and federal authority. That’s more than a history lesson. That’s about being able to hold multiple perspectives in tension, something we all need more practice with in and out of school.

Synthesizing Messages: In the Manifest Destiny lesson, the MiniReport asked students to combine ideas from a traditional textbook and a more critical, modern article. They had to make sense of competing viewpoints and turn it into a coherent written product. That’s the kind of synthesis skill that transfers to writing, speaking, and decision making.

Asking the Right Questions: Wicked Hydra helped students generate their own questions from a provocative headline. We didn’t start with answers – we started with curiosity. That habit of inquiry matters. It helps students know what to ask when things get unclear or when they need to dig deeper, whether it’s in history or real life.

Final Thoughts

When I rack and stack, I’m not just filling time or tossing in a protocol because it’s fun. I’m designing a flow. A lesson that moves students from buiulding background knowledge/retrieval to confident creation – without burning them out along the way.

Even though the topics change, the thinking stays consistent:

Start with the goal

Build the sequence that supports the right kind of thinking

Keep the cognitive load manageable

Let students do the heavy lifting, at the right time, with the right support

If you’re just getting into racking and stacking, here’s my best advice:

Start small. Pay attention to the thinking each step requires. And when in doubt, ask: What do I want students to do with their brain next? That’s the question that drives everything I build.